Recommended for grades 6-12

In this resource, you’ll:

-

Meet Duke Ellington and discover the path he took to become a musician.

-

Learn how Duke Ellington’s musical style evolved over his career.

-

Explore the storytelling in Ellington’s Harlem.

In this resource, you’ll:

Meet Duke Ellington and discover the path he took to become a musician.

Learn how Duke Ellington’s musical style evolved over his career.

Explore the storytelling in Ellington’s Harlem.

Known as one of the most prominent artists in the world of jazz, ​Edward Kennedy “Duke” Ellington had one overwhelming passion as a young person in Washington, D.C.—baseball. His love of baseball was so strong (his first job was selling peanuts at Washington Senators games) that he neglected his piano studies and his piano teacher, Mrs. Clinkscales, had to perform the right-hand melodies for him when he played in recitals. But as a young teen​,​ Ellington began frequenting the raucous gambling hall known as Frank Holliday’s Pool Room, where he was surrounded by jazz pianists that inspired him, and soon his love of music eclipsed his love of the game.

Known as one of the most prominent artists in the world of jazz, ​Edward Kennedy “Duke” Ellington had one overwhelming passion as a young person in Washington, D.C.—baseball. His love of baseball was so strong (his first job was selling peanuts at Washington Senators games) that he neglected his piano studies and his piano teacher, Mrs. Clinkscales, had to perform the right-hand melodies for him when he played in recitals. But as a young teen​,​ Ellington began frequenting the raucous gambling hall known as Frank Holliday’s Pool Room, where he was surrounded by jazz pianists that inspired him, and soon his love of music eclipsed his love of the game.

With his new determination, Ellington focused his energy on music. He learned James P. Johnson’s “Carolina Shout” by slowing down the roll in a player piano and placing his hands on the moving keys to memorize the song. By the age of 15, he’d written his first original piece for piano, “Soda Fountain Rag”.

Starting in the early 20th century, Black Americans looking for refuge from oppressive Jim Crow laws in the South flocked to urban areas like Harlem in New York City. This massive relocation, now known as the Great Migration, resulted in the convergence of strong voices and talent, and led to the flourishing artistic, political, and cultural movement known as the Harlem Renaissance (1917-1935).

Duke Ellington and group in Louis Thomas’ cabaret, 901 R St. NW in Washington DC. (New York Public Library)

In the early 1920s, Ellington split his performance time between Harlem and Washington, DC​, eventually settling in New York, where the elegance and the sophistication of his music reflected ​New York’s ​sense of community pride and prosperity. In Harlem, Ellington was mentored by pianist Willie “the Lion” Smith and collaborated with great artists like pianist Fats Waller and saxophonist Sidney Bechet.

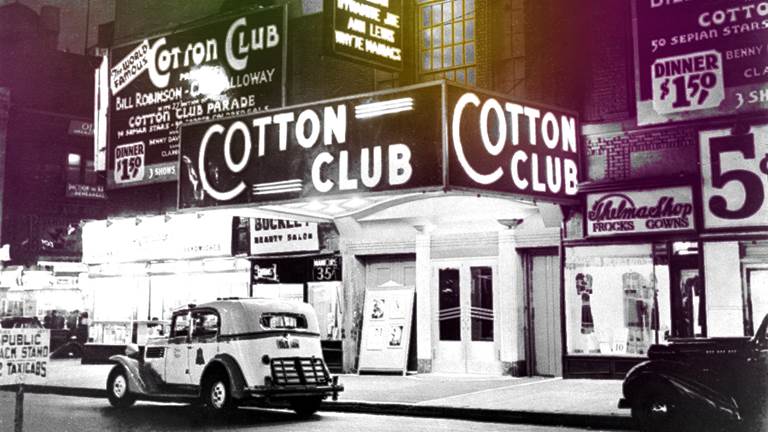

Duke Ellington with his orchestra at the Cotton Club sometime in the 1930s. (Jazzmen 1939)

In 1927​,​ he began an extended residency as a bandleader at Harlem’s legendary Cotton Club, where he received national and international exposure through radio and a recording career through the emerging format of 78rpm record albums*.

The Duke Ellington band in the recording studio, mid 1930s (The Steven Lasker Collection)

Ellington and his band excelled at the 78rpm format, with many of their recordings becoming jazz standards that are still played today: “East St. Louis Toodle-Oo” (1927), “Mood Indigo” (1930), “Sophisticated Lady” (1932), “It Don’t Mean a Thing (If it Ain’t Got That Swing)” (1932), “Don’t Get Around Much Anymore” (1940), and “Satin Doll” (1953).

*The 78rpm format refers to the record spinning at 78 revolutions per minute, which is quite fast when compared to modern vinyl records, which spin at about 33 revolutions per minute. Each side of a 78rpm record would typically hold under five minutes of music.

“I am putting all I have learned into it in the hope that I shall have achieved something really worthwhile in the literature of music, and that an authentic record of my race​​ written by a member of it shall be placed on record.”

The Duke Ellington Orchestra in the 1943 film Reveille with Beverly. (Getty Images)

Ellington and his band recorded on multiple record labels under different names: The Washingtonians, the Whoopee Makers, the Six Jolly Jesters, the Memphis Hot Shots, Duke Ellington and his Cotton Club Orchestra, Duke Ellington and His Famous Orchestra, and many others.

Ellington’s celebrity would even expand to Hollywood. He made many appearances on the big screen, starting with the short film Black and Tan in 1929 and the feature film Check and Double Check in 1930. Ellington believed the greatest praise in the arts was to be “beyond category.”

Black and Tan, directed by Dudley Murphy. 1929, RKO Radio Pictures

Ellington began to feel confined by the limitations of the 78rpm format on his music. Ellington’s first departure from these constraints was on his 1931 recording of “Creole Rhapsody,” which had to be split into two sections, one per side of the record. He credited that departure from the norm as “the seed from which all kinds of extended works and suites later grew.”

Billy Strayhorn and Duke Ellington, 1943 (The Duke Ellington Society)

But Ellington didn’t abandon the popular short form jazz “single” format. In 1938, Ellington met pianist and composer Billy Strayhorn, leading to a three-decade writing partnership. Compositions that Strayhorn contributed to Duke Ellington’s orchestra include “Johnny Come Lately” (1942), “Rain Check” (1942), and “Lush Life” (1948). Their most famous collaboration, “Take the ‘A’ Train” (1939), was written when Ellington gave Strayhorn directions to his home in Harlem.

Ellington’s writing expanded into long-form multi-part suites, starting with Black, Brown and Beige in 1943, and ​he ​continued​ to expand the instrumentation of his orchestra. Though the trend in the late 1940s was smaller jazz ensembles and combos, Ellington would continue to employ a full-size jazz orchestra of hand-picked musicians with whom he would tour throughout his career, funding them with the royalties from the sales of his popular “singles.”

A large crowd welcomes Duke Ellington on his arrival at Gare du Nord in Paris, 1948. (Keystone-France/Gamma-Rapho/Getty)

“The writing and playing of music is a matter of intent... You can’t just throw a paintbrush against the wall and call whatever happens art. My music fits the tonal personality of the player. I think too strongly in terms of altering my music to fit the performer to be impressed by accidental music. You can’t take doodling seriously.”

In 1950, Duke Ellington received a commission from NBC Symphony Orchestra director Arturo Toscanini, which resulted in the composition Harlem, a fourteen-minute symphonic jazz suite celebrating the vibrancy and culture of his adopted home of Harlem in New York City.

125th Street and Lenox Avenue, Harlem, in the 1950s (harlemworldmagazine.com)

Harlem tells a non-narrative story. Ellington offers musical visualizations as inspiration​.​ Listeners are invited to create a story using their own imaginations in response to themes and mood changes in the music, both in aspirational civil rights progress and the simpler activities of daily life.

Improvisation is a defining characteristic of jazz. Jazz composers devote whole sections of compositions to allow soloists space to improvise. Improvisations are based on chord changes and melody, but they are based in spontaneous expressions of musical creativity.

In Harlem, Ellington took the inspiration of improvisation and crafted fully defined “solos” based on his knowledge of the performance practices of the individual players in his orchestra. This brought his approach closer to the practices of the classical orchestral approach, where composers almost always notate exactly what the players should play (though some baroque-era concertos include a cadenza where the soloist is encouraged to improvise on the composer’s themes).

Ellington’s orchestra was not just instruments, ​​it was people with musical personalities. As the membership changed, so did the arrangements​.​ It was through the intimate appreciation of each musician’s sound that Ellington was able to craft compositions and arrangements that both highlighted each player’s tone and even calculated the way in which they would tend to improvise. By crafting bespoke approaches to improvisatory passages through combining techniques from both​ jazz and classical music, Ellington’s work was exactly what he desired it to be: beyond category.

Harlem Excerpt 1 - Largo / Medium Swing

Harlem begins on a Sunday morning, with well-dressed people heading to and from church. In Ellington’s words, “you may hear a parade go by, or a funeral, or you may recognize the passage of those who are making Civil Rights demands. Hereabouts in our performance, Cootie Williams pronounces the word on his trumpet – “Harlem!””

Williams uses a plunger mute as a tool to imitate the human voice with his trumpet. As he plays, the orchestra answers his solo trumpet call with chords. This elegant call-and-response section is played rubato, with a loose and free sense of time, and the instruments taking turns proclaiming the title of the piece.

Harlem Excerpt 2 - Fast Rhumba / Swing / Bebop

Ellington takes us up 7th Avenue through the Spanish and West Indian neighborhood toward 125th Street. The drummer shifts into a dramatic mood and tempo change, alternating between an uptempo Latin groove and an energetic swing feel, evoking a sense of moving through a bustling hub of different cultures, taking in the sights and sounds of a vibrantly rich and diverse community.

Harlem Excerpt 3 - Ad Lib / Slowly (Big Back Beat)

The mood again shifts from joyful to somber once the clarinet plays a solo haunting melodic line. This section, rich with the soulful tones of an intertwined trombone and clarinet lines, drags with the mournful swagger of a New Orleans jazz funeral dirge. The energy becomes increasingly optimistic as the screaming trumpets and swinging percussion trade off with the more intimate solo brass and reed sections.

Harlem Excerpt 4 - Faster

Latin percussion takes center stage as we near the finale that pushes the brass to their limit. Just like in jazz funerals, Harlem ends in grandiose fashion with a celebration of life.

“I think the music situation today has reached the point where it isn’t necessary for categories. I think what people hear in music is either agreeable to the ear or not. And if this is so, if music is agreeable to my ear, why does it have to have a category?”

Harlem received mixed reviews upon its premiere (jazz critic James Lincoln Collier suggested that the work was underdeveloped and incohesive, while President Harry Truman expressed honor at being presented with the original score to Harlem by Ellington himself). But Ellington’s abstract musical storytelling became a common approach for jazz orchestra compositions by many celebrated composers. Harlem has been performed by many notable orchestras, including the Lincoln Center Jazz Orchestra, the Boston Symphony Orchestra, The Los Angeles Philharmonic Orchestra, and the Paris Symphony Orchestra.

Ellington’s career continued to expand beyond category through the latter half of the 20th century. In 1959 he wrote the score for the film Anatomy of a Murder, followed by Paris Blues in 1961. He composed a prolific catalog of jazz suites, which reflected his observations of people and of society, art, poetry and life in general:

Duke Ellington won 14 Grammy awards, received a posthumous Pulitzer Prize for music in 1999, was presented the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 1969, a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame, and is the namesake of the Duke Ellington School of the Arts in Washington, DC (established in 1974). His legacy and music continue to influence artists and push beyond the categories of music.

|

Music Player

|

Duke Ellington & Billy Strayhorn

|

|

Symphonic Suites & Film Scores

|

Writers

Mark Braud

Kenny Neal

Editors

Alyssa Kariofyllis

Tiffany A. Bryant

Producer

Kennedy Center Education Digital Learning

Updated

January 2024

Meet the actors, musicians, artists, dancers, writers, activists, and supporters of the early 20th century Harlem Renaissance, and discover the creative, cultural, and political “intersections” they made with each other.

From Fairmont Street to U Street, from the Howard Theater to the Bohemian Caverns, take a tour through jazz history with Billy Taylor and Frank Wess, who lead listeners through their hometown’s music scene in this seven-part audio series.

In this Kennedy Center commission, two of today’s top vocalists explore how classical sounds intertwine with improvisational jazz in the music of Duke Ellington, blending European classical traditions with syncopated rhythms and African American work songs, blues, and spiritual music.

This series, hosted by Connaitre Miller of Howard University, explores why Swing was the most popular dance music in America and how it is still alive today in dance halls, clubs and movies

Generous support for educational programs at the Kennedy Center is provided by the U.S. Department of Education.

Gifts and grants to educational programs at the Kennedy Center are provided by The Paul M. Angell Family Foundation; Bank of America; Capital One; The Morris and Gwendolyn Cafritz Foundation; Carnegie Corporation of New York; The Ednah Root Foundation; Harman Family Foundation; William R. Kenan, Jr. Charitable Trust; the Kimsey Endowment; The Kiplinger Foundation; Laird Norton Family Foundation; Lois and Richard England Family Foundation; Dr. Gary Mather and Ms. Christina Co Mather; The Markow Totevy Foundation; Dr. Gerald and Paula McNichols Foundation; The Morningstar Foundation; Myra and Leura Younker Endowment Fund; The Irene Pollin Audience Development and Community Engagement Initiatives;

Prince Charitable Trusts; Dr. Deborah Rose and Dr. Jan A. J. Stolwijk; Rosemary Kennedy Education Fund; The Embassy of the United Arab Emirates; The Victory Foundation; The Volgenau Foundation; Volkswagen Group of America; Jackie Washington; GRoW @ Annenberg and Gregory Annenberg Weingarten and Family; Wells Fargo; and generous contributors to the Abe Fortas Memorial Fund and by a major gift to the fund from the late Carolyn E. Agger, widow of Abe Fortas. Additional support is provided by the National Committee for the Performing Arts..

The content of these programs may have been developed under a grant from the U.S. Department of Education but does not necessarily represent the policy of the U.S. Department of Education. You should not assume endorsement by the federal government.